“Everybody has plans until they get hit the first time.” — Mike Tyson

An economist was once asked, “If you were stranded on a desert island, how would you survive?” The economist pondered this great question for some time and then proudly ventured his answer: “Assume a perfect world…” — old joke about economists

I am not known for my love of business or management books; quite the opposite, actually. When I try to articulate why, it generally comes down to boredom and a decided lack of enthusiasm for the subject. It’s not that I don’t appreciate the appeal of business topics or the act of conducting it. Far from it. It’s more that there’s an utter futility to the idea that we can do it better. I led off this post with the 2 quotes above to illustrate my reasoning. They seem to come from very different points of view, and yet they are in my mind very much related:

- Business books are not reflective of lived experiences or real world incentives, just like the economist in the above example, and…

- They’re hopelessly naive and unable to account for what happens the first time a practitioner gets “punched in the face” (not literally, of course, or at least not usually)

Both quotes illustrate the difficulty of putting a plan into action, either because you didn’t account for resistance (Mike Tyson) or the realities of the real world constraints (the economist). I dislike business books for the same reason I dislike management consultants, strategists, market analysts, pundits, and any other pointy-haired expert who tries to tell me how to do my job better: because their words prove to be almost useless against the realities of functioning, much less thriving, in a real-life bureaucratic system. With that in mind, I’m now going to do what I probably never should: give advice on how to be a change agent in large bureaucratic organizations. Given what I wrote above, you could be forgiven for asking, “Why?” The answer is rather simple: despite all my experience which tells me I should really know better, at the end of the day, I naively follow an insatiable desire to drive change. Knowing better or not, it doesn’t stop me from trying. The act of futile resistance against the borg is buried deep, deep inside my psyche. It’s terminal, I’m afraid.

Never, Ever be a Change Agent

The first thing to know about being a change agent is to not be one. Just don’t do it. No one is ever going to congratulate you on your futility or give you an award for repeatedly beating your head against countless walls. Just don’t. The best that can happen is that somebody else advances themselves based on your ideas, picks up the pieces after you’ve been beaten to a pulp, and then gets the accolades. The worst that can happen is that nobody every listens to you at all and you toil away in silence and isolation, walled off from doing any real damage. Note that getting fired is not the worst outcome. In fact, it’s a great way to confirm you were on to something and extricate yourself from a terrible situation, preventing you from expending energy on fruitless efforts that nobody will acknowledge. Getting fired is a merciful end. Futilely trudging along with no end in sight? Now that’s inhumane torture.

To successfully make changes in an organization, think very carefully about who you need to convince and bring along for the ride: your upper management. That’s right, the very people who have benefited from the existing systems. Remind me, what is their incentive for changing? Their interest goes only as far as their incentives. To be a successful change agent, you have to convince them that change is in their interest, and that’s a pretty high bar. To be successful, your leaders have to be in such a position that they see an urgent need for change that will benefit the organization – but also simultaneously benefit them. The stars have to be aligned just so, and you will need to take extra care to spot the right opportunities. I cannot emphasize this point enough: the stars do not tend to align except in particular circumstances. You have to learn to be very adept at spotting those particular circumstances. As I said, most of the time it’s not worth it.

For the remainder of this post, I’m going to assume that you are disregarding my hard-earned, well-considered advice and have chosen to proceed on this adventure in masochism.

Ok, Fine. You’re a Change Agent. Now What?

The first thing to know about large organizations is that they never fail. Where most change agents go wrong is they erroneously assume that organizations are failing. If you are asking the question, “why is this organization failing?” know that you are asking precisely the wrong question. Organizations behave exactly as they are designed, and one thing they are designed to do is to resist change. When you zoom out and consider the possible outcomes of an organization’s lifecycle, this is not a bad thing. A long-lived organization will need to be able to survive the whims and myopia of misguided leaders as well as the ups and downs of its industry and market. Resistance to change is a design feature, not a bug. Organizations are so good at self-perpetuation that they are quite adept at identifying and neutralizing potential threats, ie. people that want to change things. How this happens depends on the environment, from putting you on projects that keep you tied up (and away from the things management cares about) to just flushing you out entirely if you prove too meddlesome.

This is why I get annoyed with most attempts to affect change: they assume that organizations need to be better, and they assume that their pet project is a way to do that. Thus we have movements like Agile and DevOps, which started off as a means to change organizations and eventually were subsumed by the beast, becoming tools that organizations use to perpetuate their existence without actually changing anything. The authors of the Agile manifesto wanted to change how technology worked in organizations, but what they actually did was give large organizations the language they needed to perpetuate the same incentive structures and bureaucracy they always had. DevOps was going to put Agile methodology into practice and empower (whatever that means) technologists to take a larger stake in the business. I’m pretty sure CIOs are still laughing about that one. In the meantime, we still get design by committee, the inability to make decisions, and endless red tape to prevent change from actually happening. Again, this isn’t necessarily bad from the perspective of a business built to last; it’s just really annoying if you expect things to move after you push. My advice: adjust your expectations.

Incentives and Human Behavior

The reason most change initiatives fail is because they don’t account for the reality of incentives and the influence of human behavior. Large organizations have evolved intricate systems of carrots and sticks to reward certain behaviors and punish or at least discourage behaviors deemed impolitic. Want to know why teams don’t collaborate across organizations? Because they’re not rewarded for doing so. Why do leaders’ edicts get ignored? Because teams are incentivized to stay the course and not switch abruptly.

Agile failed in its original intent because it naively assumed that incentives would be aligned with faster development and delivery of technology. What it failed to calculate was that any change in a complex system would incur a premium cost or tax for the change. Any change to a legacy system with complex operations will have unknown consequences and therefore unknown costs. The whole point of running a business effectively is to be able predict P&L with some accuracy. Changes to legacy systems incur necessary risk, which disincentivizes organizations from adopting them at scale. Thus agile morphs from accelerated development and delivery to a different type of bureaucracy that served the same purpose as the old one: preventing change. Except now it uses fancy words like “scrums”, “standups”, and “story points”. As Charles Munger put it, “show me the incentives, and I’ll show you the outcome.” If the avoidance of risk is incentivized and rewarded, then practitioners in your organization will adopt that as their guiding principle. If your employees get promoted for finishing their pet projects and not for collaborating across the organization, guess what they will choose to do with their time?

It’s this naive disregard of humanity that dooms so many change initiatives. Not everyone wants to adopt your particular changes, and there may be valid reasons for that. Not everyone wants to be part of an initiative that forever changes an organization. Some people just want to draw a paycheck and go home. To them, change represents risk to their future employment. Any change initiative has to acknowledge one universal aspect of humanity: to most people, change is scary. Newsflash: some people don’t tie their identities to their jobs. I envy them, honestly. And still others aren’t motivated to change their organization. They are just fine with the way things are.

Parasite-Host Analogy

And how do organizations prevent change? By engaging in what I call the “host immune response.” If you’re familiar with germ theory and disease pathology you know that most organisms have evolved the means to prevent external threats from causing too much harm. Mammals produce mucous, which surrounds viruses and bacteria in slimy goo to prepare for expulsion from the body, preventing these organisms from multiplying internally and causing damage to organs. Or the host will wall off an intruder, not eradicating or expelling it, just allowing it to exist where it can’t do any damage, like a cyst. Or an open source community.

Within this host immune response and parasite analogy, there lies the secret to potential success: symbiosis. If you recall your high school biology textbook (and really, who doesn’t?) you’ll recall that symbiosis is the result of 2 species developing a mutually beneficial relationship. Nature provides numerous examples or parasitic relationships evolving into symbiosis: some barnacle species and whales; some intestinal worms and mammals; etc, etc. In this analogy, you the change agent are the parasite, and the organization you work for is the host. The trick is for the parasite to evade getting ejected from the host. To do that, the parasite has to be visible enough for its benefits to be felt, but not so visible as to inflame the host. It’s quite the trick to pull off. To put this into more practical terms, don’t announce yourself too loudly, and get in the habit of showing, not telling.

Oh dear… I’ve now shifted into the mode of giving you a ray of hope. I’m terribly sorry. I fear that my terminal case of unbridled optimism has now reared its ugly head. Fine. Even though it’s probably pointless and a lost cause, and you’re only signing up for more pain, there are some things you can do to improve your chances of success from 0% to… 0.5%?

Show, Don’t Tell

There are few things large organizations detest more than a loud, barking dog. The surest route to failure is to raise the expectations of everyone around you. This is a thing that happens when you talk about your vision and plant the seeds of hope.

Stop. Talking.

Open source projects serve as a great point of reference here. Sure, many large open source projects undergo some amount of planning, usually in the form of a backlog of features they want to implement. Most well-run, large open source projects have a set of procedures and guidelines for how to propose new features and then present them to the core team as well as the community-at-large. Generally speaking, they do not write reams of text in the form of product requirements documents. They will look at personas and segmentation. They will create diagrams that show workflows. But generally speaking, they lead with code. Documentation and diagrams tend to happen after the fact. Yes, they will write or contribute to specifications, especially if their project requires in-depth integration or collaboration with another project, but the emphasis is on releasing code and building out the project. Open source projects serve as my point of reference, so imagine my surprise when I started working in large organizations and discovered that most of them do precisely the opposite. They write tomes of text about what they are thinking of building and what they wish to build, before they ever start to actually build it. This runs counter to everything I’ve learned working in open source communities. Given my above points about not changing too much too quickly, what is a change agent to do?

Prototype. Bootstrap. Iterate.

Open Source innovation tells us that the secret to success is to lead with the code. You want to lead change? Don’t wait for something to be perfect. Do your work in the open. Show your work transparently. Iterate rapidly and demonstrate continuously. Others will want to create the PRDs, the architectural documents, the white papers, and the other endless reams of text that no one will ever read. Let them. It’s a necessary step – remember, your job is to not trigger the host immune response. You can do that by letting the usual processes continue. What you are going to do is make sure that the plans being written out are represented in the code in a form that’s accessible to your target audience as quickly as possible, and that you get it in front of your target audience as soon as it’s available. Without a working representation of what is being proposed, your vision is wishful thinking and vaporware.

The reasons are simple: if you expend your time and energy building up expectations for something that doesn’t exist yet, you risk letting the imaginations of your customers and stakeholders run wild. By limiting your interactions to demonstrations of what exists, the conversation remains grounded in reality. If you continuously present a grand vision of “the future” you will set the stage for allowing perfect to be the enemy of good. Your customers will have a moving target in their minds that you will never be able to satisfy. By building up expectations and attempting to meet them, you are setting the stage for failure. But with continuous iteration, you help to prevent expectations from exceeding what you are capable of delivering. There’s also the added benefit of showing continuous progress.

Borrowing from the open source playbook is a smart way to lead change in an organization, and it doesn’t necessarily need to be limited to code or software. Continuous iteration of a product or service being delivered can apply to documentation, process design, or anything that requires multi-stage delivery. By being transparent with your customers and stakeholders and bringing them with you on the journey, you give them an ownership stake in the process. This ownership stake can incentivize them to collaborate more deeply, moving beyond customer into becoming a full-fledged partner. This continuous iteration and engagement builds trust, which helps prevent the host from treating you like a parasite and walling you off.

Remember, most people and organizations don’t like change. It scares them. By progressing iteratively, your changesets become more manageable as well as palatable and acceptable. This is the way to make your changes seem almost unnoticeable, under the radar, and yet very effective, ultimately arriving at your desired outcome.

Prototype. Bootstrap. Iterate.

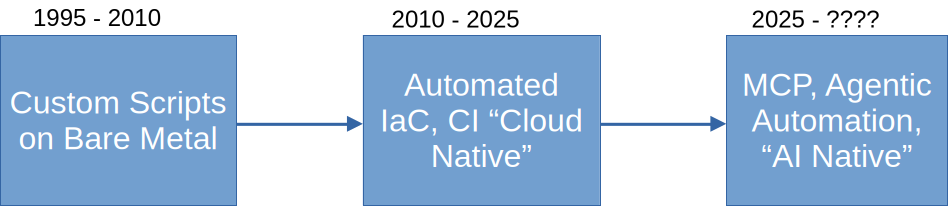

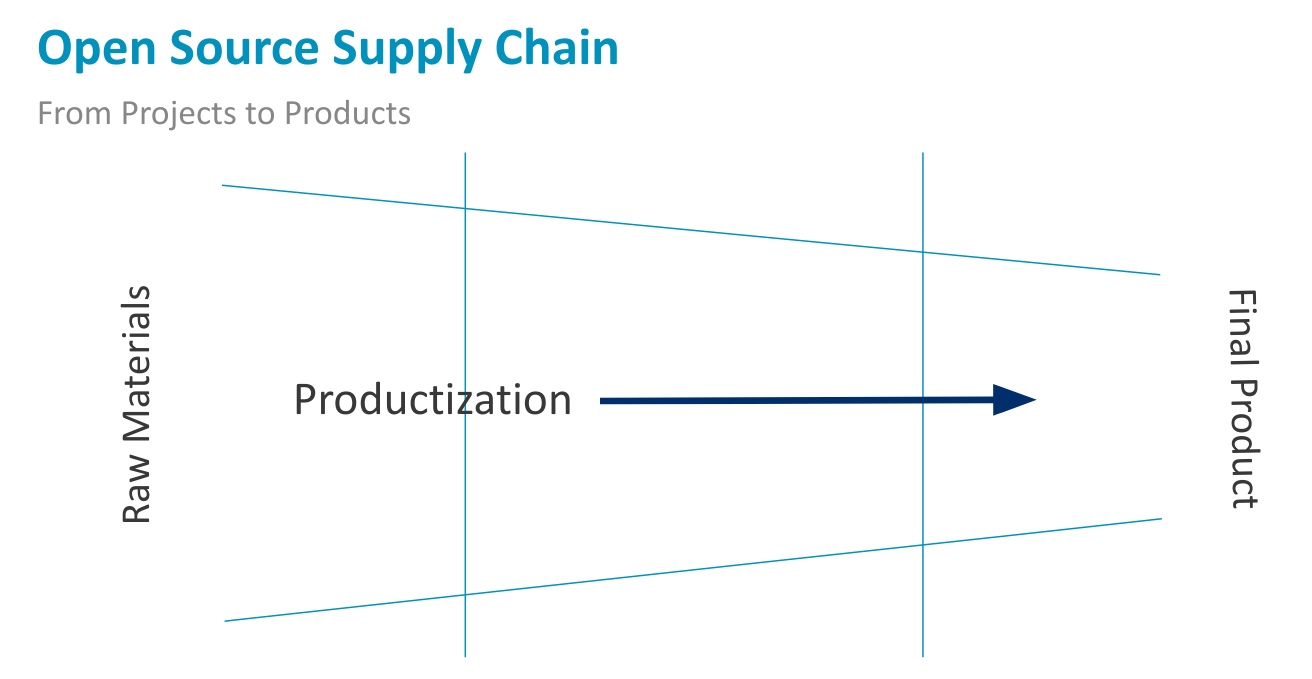

Considering that a lot of open source time and effort goes into infrastructure tooling – Kubernetes, OpenTofu, etc – one might draw the conclusion that, because these many of these tools are about to be disrupted and made obsolete, therefore “OMG Open Source is over!!11!!1!!”. Except, my conclusion is actually the opposite of that. I’ll explain.

Considering that a lot of open source time and effort goes into infrastructure tooling – Kubernetes, OpenTofu, etc – one might draw the conclusion that, because these many of these tools are about to be disrupted and made obsolete, therefore “OMG Open Source is over!!11!!1!!”. Except, my conclusion is actually the opposite of that. I’ll explain.