Back in the early days of open source software, we were constantly looking for milestones to indicate how far we had progressed. Major vendor support: check (Oracle and IBM in 1998). An open source IPO: check (Red Hat and VA Linux in 1999). Major trade show: check (LinuxWorld in 1999). And then, of course, a venture-backed startup category: check (beginning with Cygnus, Sendmail, VA, and Red Hat in the late 90’s, followed by a slew of others, especially after the dot bomb faded after 2003). Unfortunately, VC involvement came with a hefty price. And then, of course, our first VC superstar: check (Peter Fenton).

Remember, this was a world where CNBC pundits openly questioned how Red Hat could make money after they “gave away all their IP”. (spoiler alert: they didn’t. That’s why it’s so funny). So when venture capitalists got into the game, they started inflicting poor decisions on startup founders, mostly centered on the following conceits:

- OMG you’re giving away your IP. You have to hold some back! How do you expect to make money?

- Here’s a nice business plan I just got from my pal who’s from Wharton. He came up with this brilliant idea: we call it ‘Open Core’!”

- Build a community – so we can upsell them!

- Freeloaders are useless

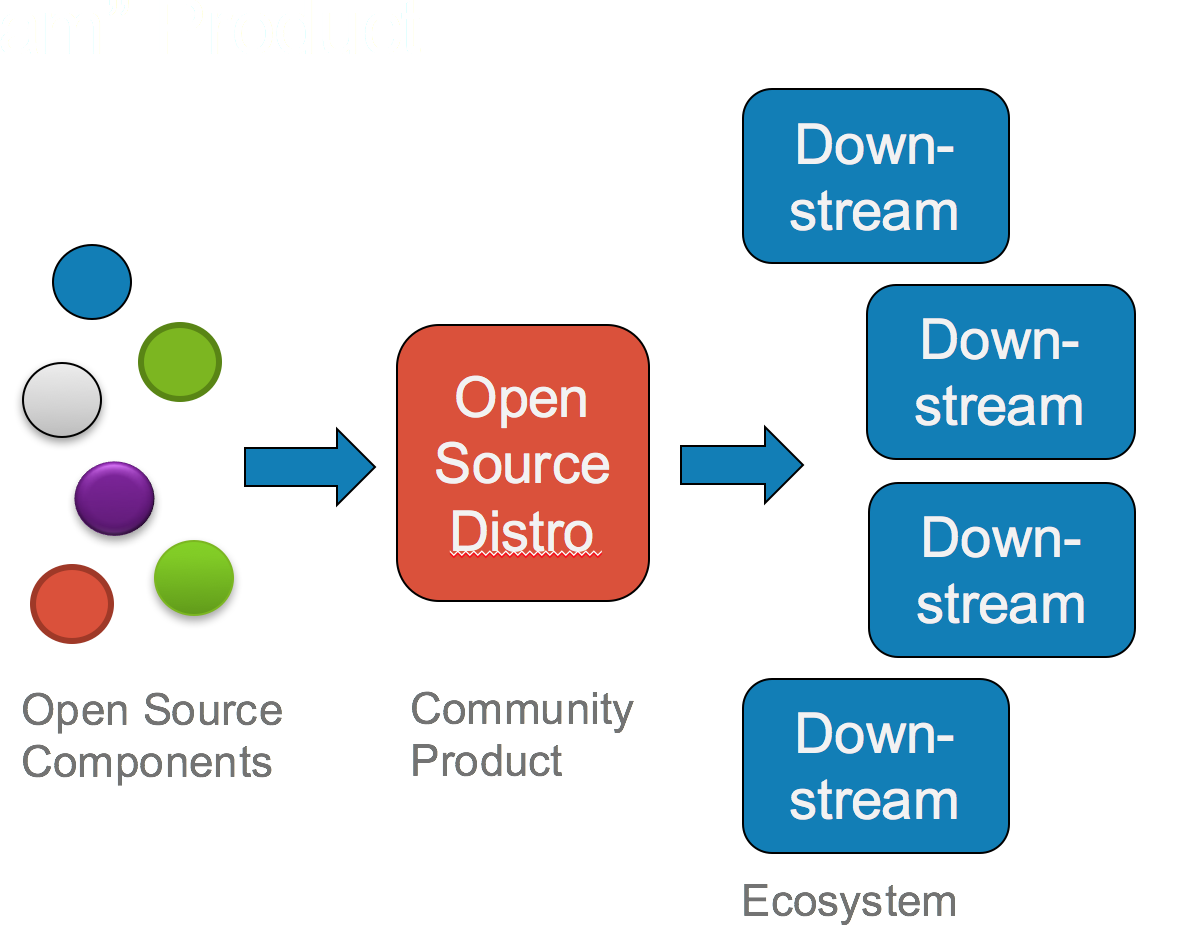

A VC’s view of open source at the time was simplistic and limited mostly to the view that a vendor should be able to recoup costs by charging for an enterprise product that takes advantage of the many stooges dumb enough to take in the free “community” product. In this view, a community is mostly a marketing ploy designed for a captive audience that had nowhere else to go. For many reasons, this is the view that the VC community embraced in the mid-2000’s. My hypothesis: when it didn’t work, it soured the relationship between investors and open source, which manifests itself in lost opportunities to this day.

What should have been obvious from the beginning – source code is not product – has only recently begun to get airplay. Instead, we’ve been forced to endure a barrage of bad diagnoses of failures and bad advice for startup founders. It’s so bad that even our open source business heroes don’t think you can fully embrace open source if you want to make money. The following is from Mike Olson, mostly known for his business acumen with Cloudera and Sleepycat:

The list of successful stand-alone open source vendors that emerged over that period is easy to write, because the only company on it is Red Hat. The rest have failed to scale or been swallowed.

…The moral of that story is that it’s pretty hard to build a successful, stand-alone open source company. Notably, no support- or services-only business model has ever made the cut.

As I have mentioned early and often, as has Stephen Walli, a project is not a product, and vice-versa, and it’s this conflation of the two that is a profound disservice to startups, developers, and yes, investors. Here’s the bottom line: you want to make money in a tech startup? Make a winning solution that offers value to customers for a price. This applies whether you’re talking about an open source, proprietary, or hybrid solution. This is hard to do, regardless of how you make the sausage. Mike Olson is a standup guy, and I hope he doesn’t take this personally, but he’s wrong. It’s not that “it’s pretty hard to build a successful, stand-alone open source company.” Rather, it’s hard to build a successful stand-alone company in *any* context. But for some reason, we notice the open source failures more than the others.

The failures are particularly notable for how they failed, and how little has been done to diagnose what went wrong, other than “They gave away all their IP!” In the vast majority of cases, these startups were poorly received because they either a.) had a terrible product or b.) they constrained their community to the point of cutting off their own air supply. There were of course, notable exceptions. While it wasn’t my idea of the best way to do it, MySQL turned out pretty well, all things considered. The point is, don’t judge startups based on their development model; judge them on whether they have a compelling offering that customers want.

While investors in 2017 are smarter than their 2005 cousins, they still have blinders when it comes to open source. They have distanced themselves from the open core pretenders, but in the process, they’ve also distanced themselves from potential Red Hats. Part of this is due to an overall industry trend towards *aaS and cloud-based services, but even so, any kind of emphasis on pure open source product development is strongly discouraged. If I’m a *aaS-based startup today and I approach an investor, I’m not going to lead off with, “and we’re pushing all of our code that runs our internal services to a publicly-accessible GitHub account!” Unless, of course, I wanted to see ghastly reactions.

This seems like a missed opportunity: if ever there was a time to safely engage in open source development models while still maintaining your product development speed and agility, using a *aaS model is a great way to do it. After all, winning at *aaS means winning at superior operations and uptime, which has zilch to do with source code. And yet, we’re seeing the opposite: most of the startups that do full open source development are the ones that release a “physical software download” and the SaaS startups run away scared, despite the leverage that a SaaS play could have if they were to go full-throttle in open source development.

It’s gotten to the point that when I advise startups, I tell them not to emphasize their open source development, unless they’re specifically asked about it. Why bother? They’re just going to be subjected to a few variations on the theme of “but how are you going to get paid?” Better to focus on your solution, how it wins against the competition, and how customers are falling over themselves to get it. Perhaps that’s how it always should have been, but it strikes me as odd that your choice of development model, which is indirectly and tangentially related to how you move product, should be such a determining factor on whether your startup gets funded, even more so than whether you have a potentially winning solution. It’s almost as if there’s an “open source tax” that investors factor into any funding decision involving open source. As in, “sure, that’s a nice product, but ooooh, I have to factor in the ‘open source tax’ I’ll have to pay because I can’t get maximum extraction of revenue.”

There are, of course, notable exceptions. I can think of a few venture-backed startups with an open source focus. But often the simple case is ignored in favor of some more complex scheme with less of a chance for success. Red Hat has a very simple sales model: leverage its brand and sell subscriptions to its software products. The end. Now compare that to how some startups today position their products and try to sell solutions. It seems, at least from afar, overly complicated. I suspect this is because, as part of their funding terms, they’re trying to overcome their investors’ perceptions of the open source tax. Sure, you can try to build the world’s greatest software supply house and delivery mechanism, capitalizing on every layer of tooling built on top of the base platform. Or you can, you know, sell subscriptions to your certified platform. One is a home run attempt. The other is a base hit. Guess which way investors have pushed?