I recently wrote 2 essays on the subject of AI Native Automation over on the AINT blog. The gist of them is simple:

- AI Native platforms are about to disrupt – and maybe disembowel – what we know today as devops

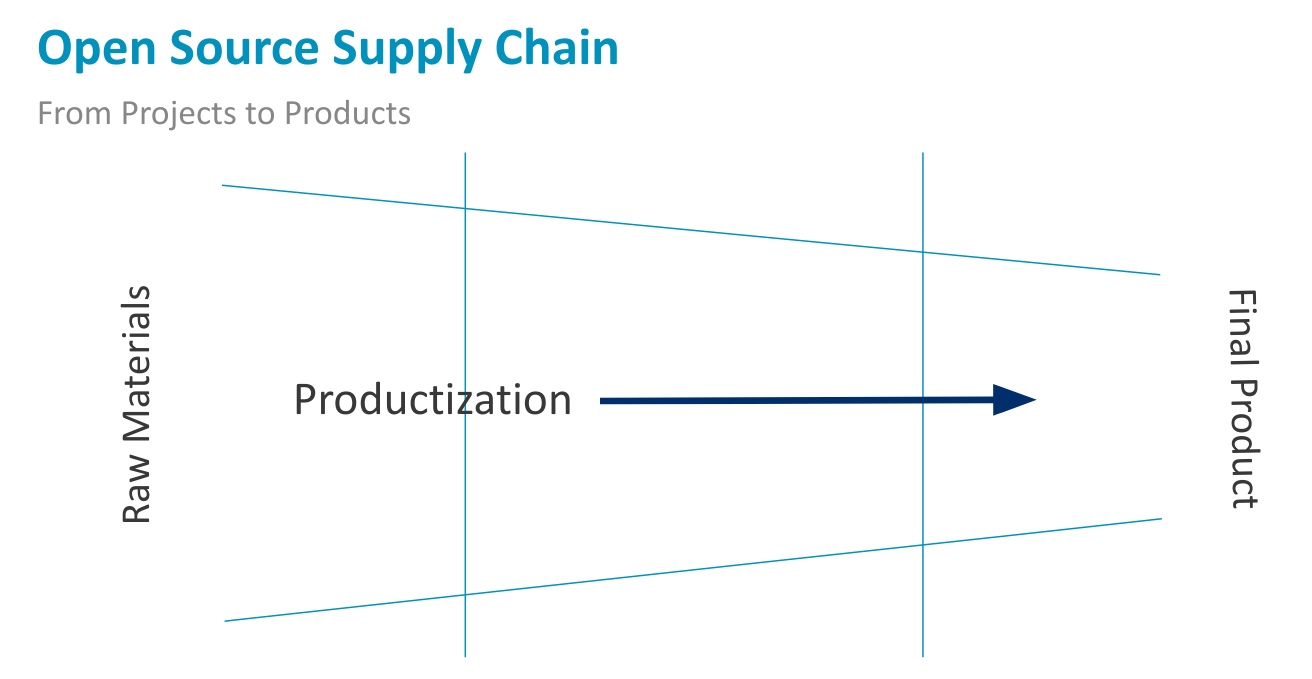

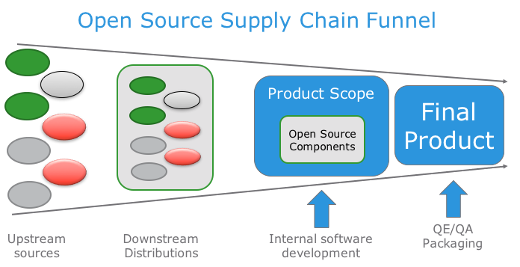

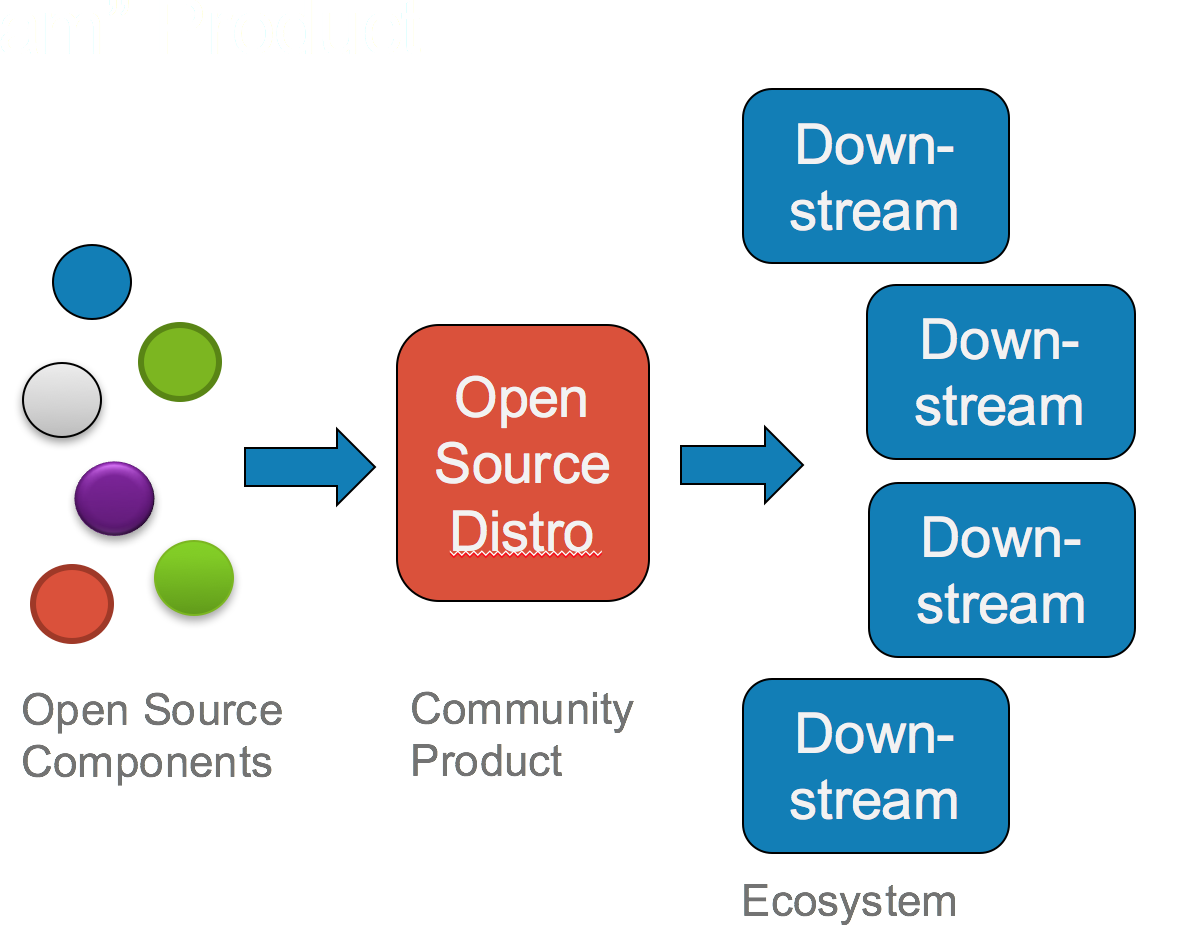

- AI Native platforms are about to dramatically increase the scope of open source ecosystems

It’s that latter point that I want to dive a bit deeper into here, but first a disclaimer:

We have no idea what the ultimate impact of "AI" is to the world, but there are some profoundly negative ramifications that we can see today: misinformation, bigotry and bias at scale, deep fakes, rampant surveillance, obliteration of privacy, increasing carbon pollution, destruction of water reservoirs, etc. etc. It would be irresponsible not to mention this in any article about what we call today "AI". Please familiarize yourself with DAIR and it's founder, Dr. Timnit Gebru.

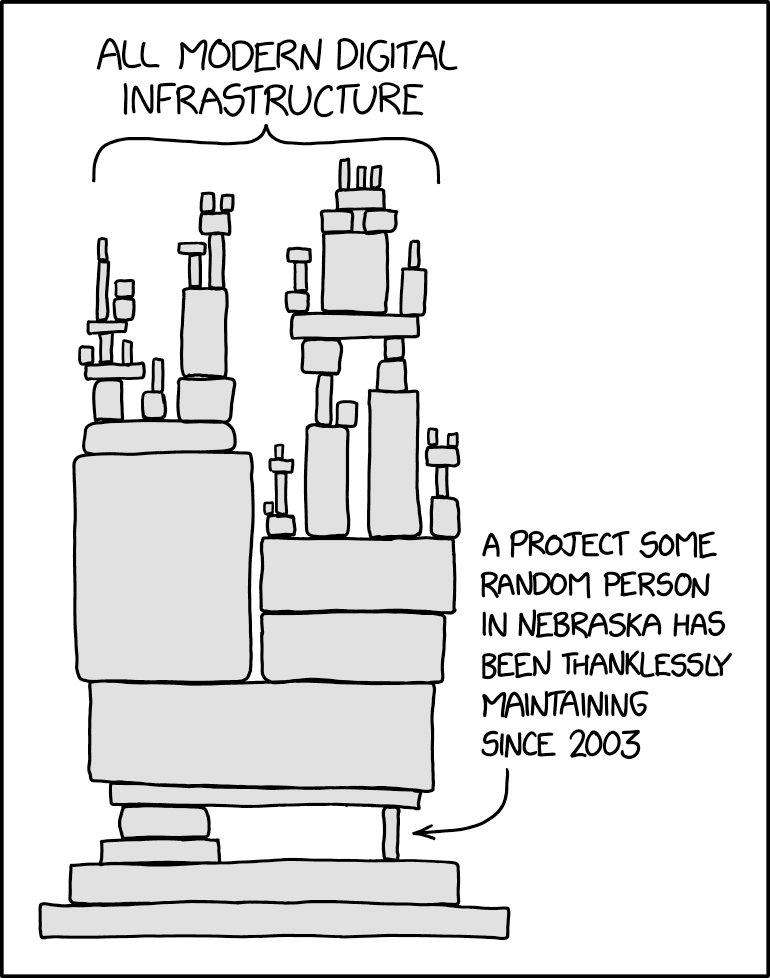

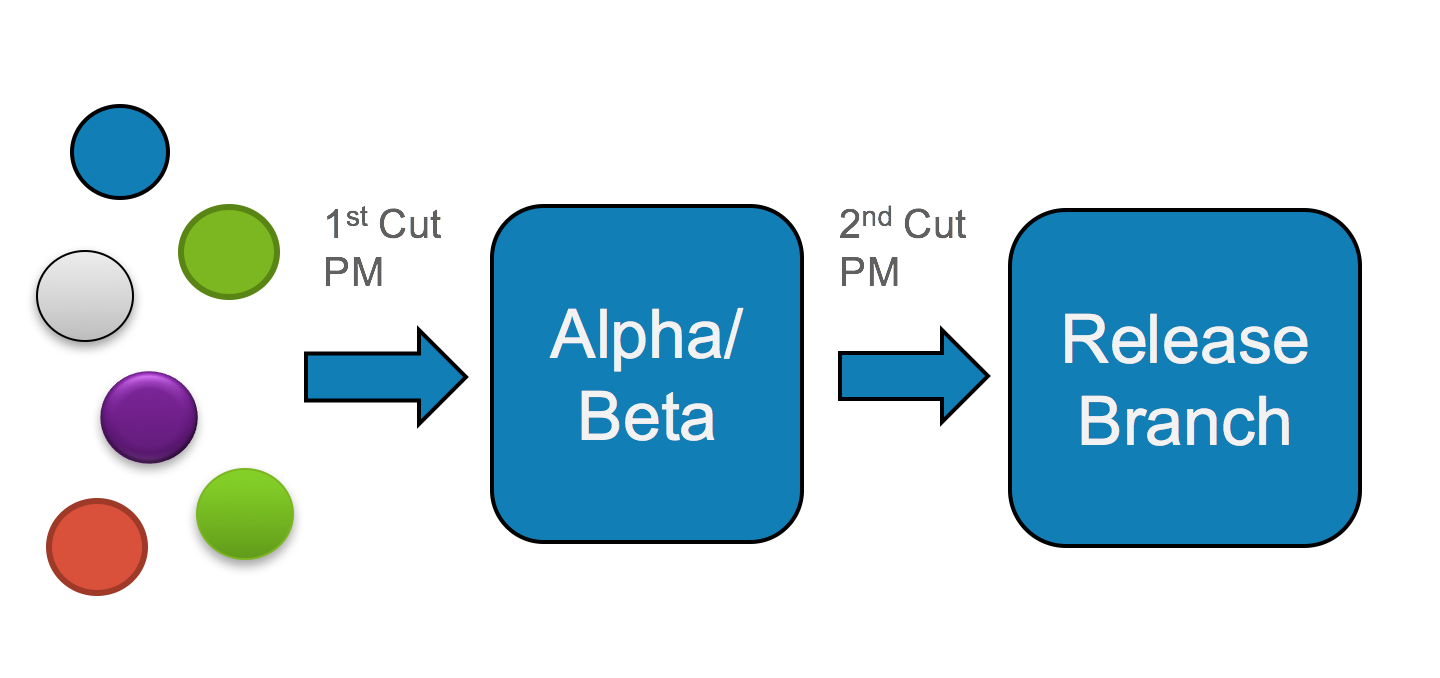

When I wrote that open source ecosystems and InnerSource rules were about to become more important than ever, I meant that as a warning, not a celebration. If we want a positive outcome, we’ll have to make sure that our various code-writing agents and models subscribe to various agreed-upon rules of engagement. The good news is we now have over 25 years of practice for open source projects at scale that gives us the basis to police whatever is about come next. The bad news is that open source maintainers are already overwhelmed as it is, and they will need some serious help to address what is going to be an onslaught of “slop”. This means that 3rd party mediators will need to step up their game to help maintainers, which is a blessing and a curse. I’m glad that we have large organizations in the world to help with the non-coding aspects of legal protections, licensing, and project management. But I’m also wary of large multi-national tech companies wielding even more power over something as critical to the functioning of society as global software infrastructure.

We already see stressors from the proliferation of code bots today: too many incoming contributions that are – to be frank – of dubious quality; new malware vectors such as “slopsquatting“; malicious data injections that turn bots into zombie bad actors; malicious bots that probe code repos for opportunities to slip in backdoors; etc – it’s an endless list, and we don’t yet even know the extent to which state-sponsored actors are going to use these new technologies to engage in malicious activity. It is a scary emerging world. On one hand, I look forward to seeing what AI Native automation can accomplish. But on the other, we don’t quite understand the game we’re now playing.

Here are all the ways that we are ill prepared for the brave new world of AI Native:

- Code repositories can be created, hosted, and forked by bots with no means to determine provenance

- Artifact repositories can have new projects created by bots with software available for download before anyone knows no humans are in the loop

- Even legitimate projects that use models are vulnerable to malicious data injections, with no reliable way to prove data origins

- CVEs can now be created by bots, inundating projects with a multitude of false positives that can only be determined by time-consuming manual checks

- Or, perhaps the CVE reports are legitimate, and now bots scanning for new ones can immediately find a way to exploit one (or many) of them and inject malware into an unsuspecting project

The list goes on… I fear we’ve only scratched the surface of what lies ahead. The only way we can combat this is through the community engagement powers that we’ve built over the past 25-30 years. Some rules and behaviors will need to change, but communities have a remarkable ability to adapt, and that’s what is required. I can think of a few things that will limit the damage:

- Public key architecture and key signing: public key signing has been around for a long time, but we still don’t have enough developers who are serious about it. We need to get very serious very quickly about the provenance of every actor in every engagement. Contributed patches can only come from someone with a verified key. Projects on package repositories can only be trusted if posted by a verified user via their public keys. Major repositories have started to do some of this, but they need to get much more aggressive about enforcing it. /me sideeyes GitHub and PyPi

- Signed artifacts: similar to the above – every software artifact and package must have a verified signature to prove its provenance, else you should never ever use it. If implemented correctly, a verified package on pypi.org will have 2 ways to verify its authenticity: the key of the person posting it, and the signature of the artifact itself.

- Recognize national borders: I know many folks in various open source communities don’t want to hear this, but the fact is that code that emanates from rogue states cannot be trusted. I don’t care if your best friend in Russia has been the most prolific member of your software project. You have no way of knowing if they have been compromised or blackmailed. Sorry, they cannot have write access. We can no longer ignore international politics when we “join us now and share the software”. You will not be free, hackers. I have to applaud the actions of The Linux Foundation and their legal chief, Michael Dolan. I believe this was true even before the age of AI slop, but the emergence of AI Native technologies makes it that much more critical.

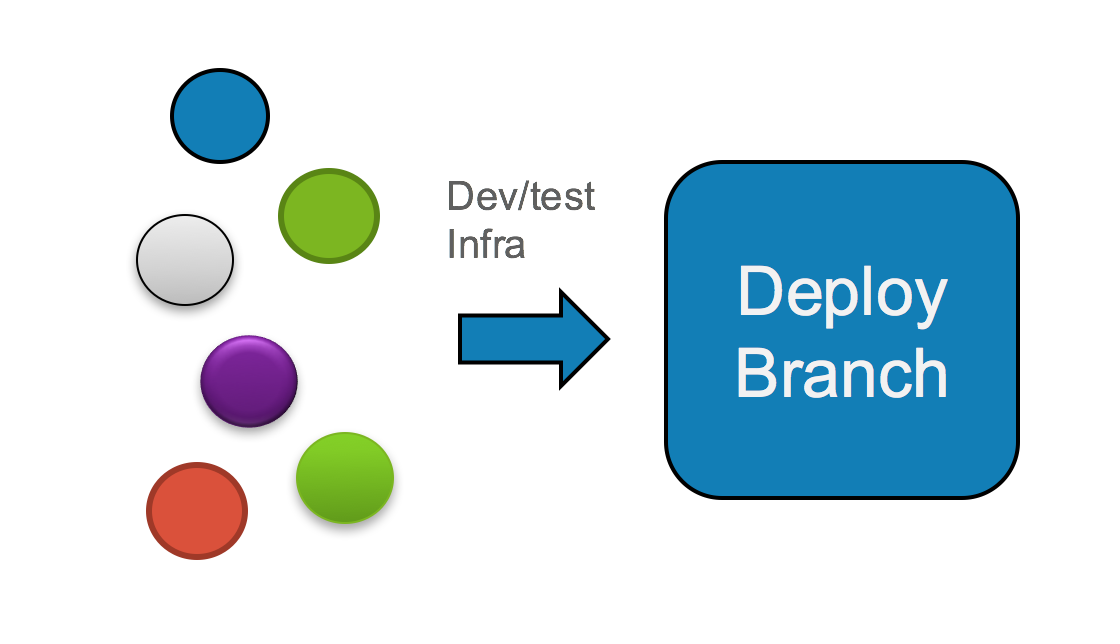

- Trust no one, Mulder: And finally, if you have a habit of pulling artifacts directly from the internet in real time for your super automated devops foo, stop that. Now. Like.. you should have already eliminated that practice, but now you really need to stop. If you don’t have a global policy for pushing all downloads through a centralized proxy repository – with the assumption that you’re checking every layer of your downloads – you are asking for trouble from the bot madness.

- Community powered: It’s not all paranoid, bad stuff. Now is a great opportunity for tech companies, individual developers, enterprises, and software foundations to work out a community protocol that will limit the damage. All of these actors can sign on to a declaration of rules they will follow to limit the damage, quarantine known bad actors, and exchange vital information for the purpose of improving security for everyone. This is an opportunity for The Linux Foundation, Eclipse, and the Open Source Initiative to unite our communities and show some leadership.

- Bots detecting bots: I was very hesitant to list this one, because I can feel the reactions from some people, but I do believe that we will need bots, agents, and models to help us with threat detection and mitigation.

I have always believed in the power of communities to take positive actions for the greater good, and now is the perfect time to put that belief to the test. If we’re successful, we can actually enjoy revamped ecosystems that will be improved upon by our AI Native automation platforms. If successful, we will have safer ecosystems that can more easily detect malicious actors. We will also have successful communities that can add new tech capabilities faster than ever. In short, if we adapt appropriately, we can accelerate the innovations that open source communities have already excelled at. In a previous essay, I mentioned how the emergence of cloud computing was both a result of and an accelerant of open source software. The same is true of AI Native automation. It will inject more energy into open source ecosystems and take them places we didn’t know were possible. But what we must never forget is that not all these possibilities are good.