This is a guest post by Paul Cormier, President, Products and Technologies, Red Hat. It was originally posted on the Red Hat blog.

Open source software is, in fact, eating the world. It is a de facto model for innovation, and technology as we know it would look vastly different without it. On a few occasions, over the past several years, software industry observers have asked whether there will ever be another Red Hat. Others have speculated that due to the economics of open source software, there will never be another Red Hat. Having just concluded another outstanding fiscal year, and with the perspective of more than 15 years leading Red Hat’s Products and Technologies division, I thought it might be a good time to provide my own views on what actually makes Red Hat Red Hat.

Commitment to open source

Red Hat is the world’s leading provider of open source software solutions. Red Hat’s deep commitment to the open source community and open source development model is the key to our success. We don’t just sell open source software, we are leading contributors to hundreds of open source projects that drive these solutions. While open source was once viewed as a driver for commoditization and driving down costs, today open source is literally the source of innovation in every area of technology, including cloud computing, containers, big data, mobile, IoT and more.

Red Hat is best known for our leadership in the Linux communities that drive our flagship product, Red Hat Enterprise Linux, including our role as a top contributor to the Linux kernel. While the kernel is the core of any Linux distribution, there are literally thousands of other open source components that make up a Linux distribution like Red Hat Enterprise Linux, and you will find Red Hatters, as well as non-Red Hatters, leading and contributing across many of these projects. It’s also important to note that Red Hat’s contributions to Linux don’t just power Red Hat Enterprise Linux, but also every single Linux distribution on the planet – including those of our biggest competitors. This is the beauty of the open source development model, where collaboration drives innovation even among competitors.

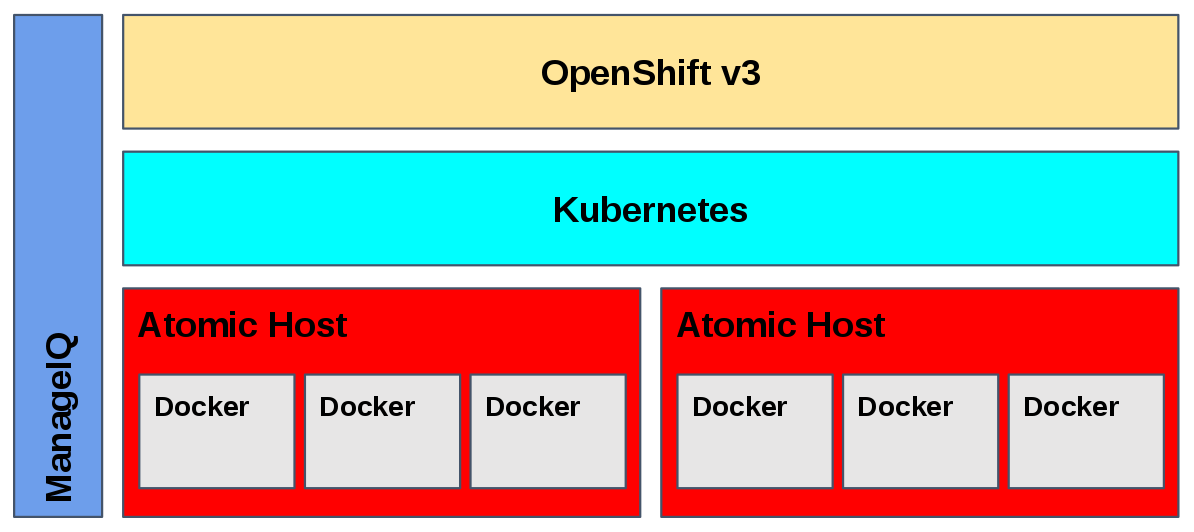

Today, Red Hat doesn’t just lead in Linux, we are leaders in many different communities. This includes well-known projects like the docker container engine, Kubernetes and OpenStack, which are among the fastest growing open source projects of the last several years. Red Hat has been a top contributor to all of these projects since their inception and brings them to market in products like Red Hat Enterprise Linux, Red Hat OpenShift Container Platform and Red Hat OpenStack Platform. Red Hat’s contributions also power competing solutions from the likes of SUSE, Canonical, Mirantis, Docker Inc., CoreOS and more.

The list of communities Red Hat contributes to includes many more projects like Fedora, OpenJDK, Wildfly, Hibernate, Apache ActiveMQ, Apache Camel, Ansible, Gluster, Ceph, ManageIQ and many, many more. These power Red Hat’s entire enterprise software portfolio. This represents thousands of developers and millions of man-hours per year that Red Hat commits to the open source community. Red Hat also commits to keeping our commercial products 100% pure open source. Even when we acquire a proprietary software company, we commit to releasing all of its code as open source. We don’t believe in open core models, or in being just consumers but not contributors to the projects we depend on. We do this because we still believe in our core that the open source development model is THE best model to foster innovation, faster.

As I told one reporter last week, some companies have endeavored to only embrace ‘open’ where it benefits them, such as open core models. Half open is half closed, limiting the benefits of a fully open source model. This is not the Red Hat way.

This commitment to contribution translates to knowledge, leadership and influence in the communities we participate in. This then translates directly to the value we are able to provide to customers. When customers encounter a critical issue, we are as likely as anyone to employ the developers who can fix it. When customers request new features or identify new use cases, we work with the relevant communities to drive and champion those requests. When customers or partners want to become contributors themselves, we even encourage and help guide their contributions. This is how we gain credibility and create value for ourselves and the customers we serve. This is what makes Red Hat Red Hat.

Products not projects

Open source is a development model, not a business model. Red Hat is in the enterprise software business and is a leading provider to the Global 500. Enterprise customers need products, not projects and it’s incumbent on vendors to know the difference. Open source projects are hotbeds of innovation and thrive on constant change. These projects are where sometimes constant change happens, where the development is done. Enterprise customers value this innovation, but they also rely on stability and long-term support that a product can give. The stable, supported foundation of a product is what then enables those customers to deliver their own innovations and serve their own customers.

Too often, we see open source companies who don’t understand the difference between projects and products. In fact, many go out of their way to conflate the two. In a rush to deliver the latest and greatest innovations, as packaged software or public cloud services, these companies end up delivering solutions that lack the stability, reliability, scalability, compatibility and all the other “ilities” or non-functional requirements that enterprise customers rely on to run their mission-critical applications.

Red Hat understands the difference between projects and products. When we first launched Red Hat Enterprise Linux, open source was a novelty in the enterprise. Some even viewed it as a cancer. In its earliest days, few believed that Linux and open source software would one day power everything from hospitals, banks and stock exchanges, to airplanes, ships and submarines. Today open source is the default choice for these and many other critical systems. And while these systems thrive on the innovation that open source delivers, they rely on vendors like Red Hat to deliver the quality that these systems demand.

Collaborating for community and customer success

Red Hat’s customers are our lifeblood. Their success is our success. Just like we thrive on collaboration in open source communities, that same spirit of collaboration drives our relationships with our customers. By using open source innovation, we help customers drive innovation in their own business. We help customers consume the innovation of open source-developed software. Customers appreciate our willingness to work with them to solve their most difficult challenges. They value the open source ethos of transparency, community and collaboration. They trust Red Hat to work in their best interests and the best interests of the open source community.

Too often open source vendors are forced to put commercial concerns over the interests of customers and the open source communities that enable their solutions. This doesn’t serve them or their customers well. It can lead to poor decision making in the best case and fractured communities in the worst case. Sometimes these fractures are repaired and the community emerges stronger, as we saw recently with Node.js. Other times, when fractures are beyond repair, new communities take the place of existing ones, as we have seen with Jenkins and MariaDB. Usually, we see that open source innovation marches forward, but this fragmentation only serves to put vendors and their customers at risk.

Red Hat believes in collaborating openly with both customers and the open source community. It’s that collaboration that brings forward new ideas and creative solutions to the most difficult problems. We work with the community to identify solutions and find common ground to avoid fragmentation. Through the newly launched Red Hat Open Innovation Labs we are bringing that knowledge and experience directly to our customers.

The next Red Hat

Will there be another Red Hat? I hope and expect that there will be several. Open source is now the proven methodology for developing software. The days of enterprises relying strictly on proprietary software has ended. The problems that we have to solve in the complexities of today’s world are too big for just one company. Vendors may deliver solutions in different ways, address different market needs and/or serve different customers – but I believe that open source will be at the heart of what they do. We see open source at the core of leading solutions from both the major cloud providers and leading independent software vendors. But, open source is a commitment, not a convenience, and innovative open source projects do not always lead to successful open source software companies.

Today, we strive not only to be the Red Hat of Linux, but also the Red Hat of containers, the Red Hat of OpenStack, the Red Hat of middleware, virtualization, storage and a whole lot more. Many of these businesses, taken independently, would be among the fastest growing technology companies in the world. They are succeeding because of the strong foundation we’ve built with Red Hat Enterprise Linux, but also because we’ve followed the same Red Hat Enterprise Linux playbook of commitment to the open source community, knowing the difference between products and projects, and collaborating for community and customer success – across all of our businesses. That’s what makes us Red Hat.

Bitnami

Bitnami