(This is the first in a series)

For the last few years, the world of commercial open source has been largely dormant, with few startup companies making a splash with new open source products. Or if companies did make a splash it was for the wrong reasons, see eg. Hashicorp’s Terraform rugpull. It got to the point that Jeff Geerling declared that “Corporate Open Source is Dead“, and honestly, I would have agreed with him. It seemed that the age of startups pushing new open source projects and building a business around them was a thing of the past. To be clear, I always thought that it was naive to think that you could simply charge money for a rebuild of open source software, but that fact that startups were always trying showed that there was momentum behind the idea of using open source to build a business.

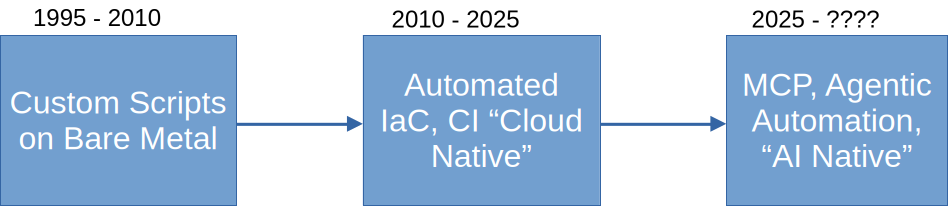

And then a funny thing happened – a whole lot of new energy (and money) started flowing into new nascent companies looking to make a mark in… stop me if you’ve heard this one… generative AI. Or to put it in other words, some combination of agents built on LLMs that attempted to solve some automation problem, usually in the category of software development or delivery. It turns out that when there’s lots of competition for users, especially when those users are themselves developers, that a solid open source strategy can make the difference between surviving and thriving. In light of this newfound enthusiasm for open source and startups, I thought I’d write a handy guide for startups looking to incorporate open source startegy into their developer go to market playbook. Except in this version, I will incorporate nuances specific to our emerging agentic world.

To start down this path, I recommend that startup founders look at 3 layers of open source go to market strategy: platform ecosystem (stuff you co-develop), open core (stuff you give away but keep IP), and product focus (stuff you only allow paying customers to use). That last category, product focus, can be on-prem, cloud hosted, or SaaS services – it won’t matter, ultimately. Remember, this is about how to create compelling products that people will pay for, helping you establish a business. There are ways to use open source principles that can help you reach that goal, but proceed carefully. You can derail your product strategy by making the wrong choices.

Foundation: the Platform Ecosystem Play

When thinking about open source strategy, many founders thought they could release open source code and get other developers to work on their code for free as a new model of outsourcing. This almost never works as the startup founders imagined. What does end up happening is that a startup releases open source code and their target audience happily uses the code for free, often not contributing back, causing a number of startups to question why they went down the open source path to begin with. Don’t be like them.

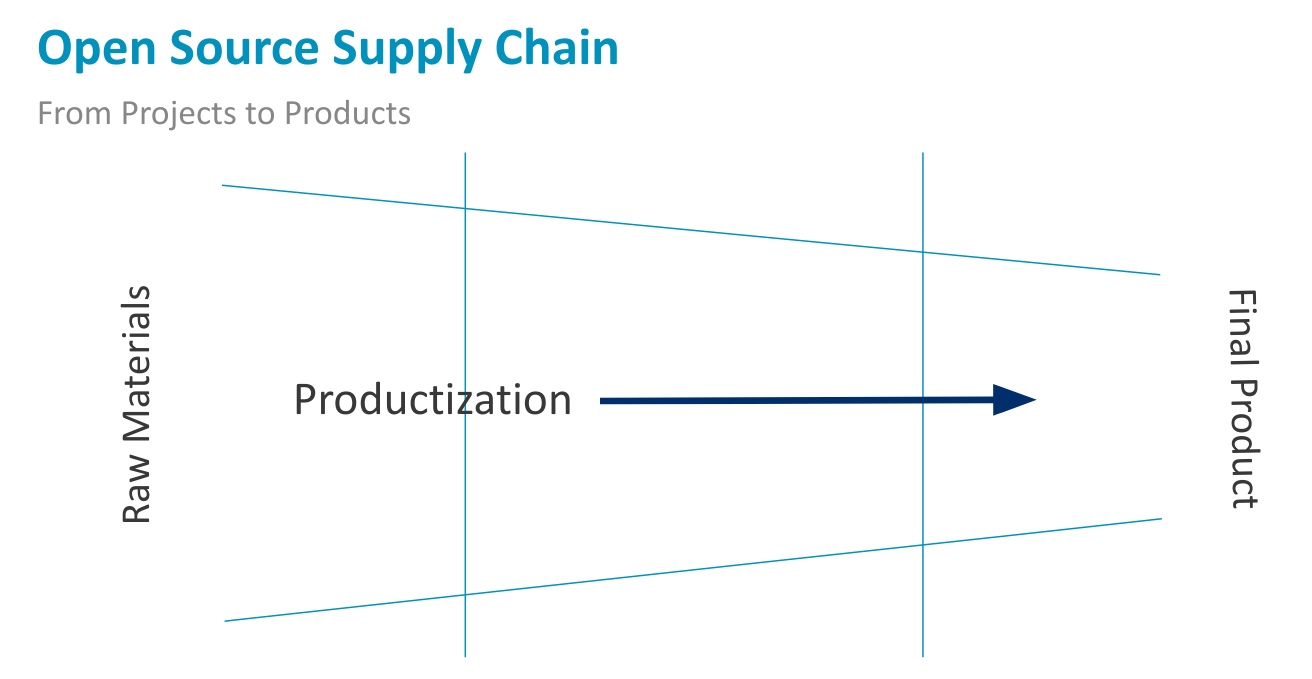

The way to think of this is within the concept of engineering economics. What is the most efficient means to produce the foundational parts of your software?

- If the answer is by basing your platform on existing open source projects, then you figure out how to do that while protecting your intellectual property. This usually means focusing on communities and projects under the auspices of a neutral 3rd party, such as the Eclipse or Linux Foundation.

- If the answer is by creating a new open source platform that you expect to attract significant interest from other technology entities, then you test product-market fit with prospective collaborators and organizations with a vested interest in your project. Note: this is a risky strategy requiring a thoughtful approach and ruthless honesty about your prospects. The most successful examples of this, such as Kubernetes, showed strong demand from the outset and their creation was a result of market pull, not a push.

- If the answer is that you don’t need external developers contributing to your core platform, but you do need end users and data on product-market fit, then you look into either an open core approach, or you create a free product that gives the platform away for free but not necessarily under an open source license. This is usually for the cases where you need developers to use or embed your product, but you don’t need them contributing directly. This is the “innovation on the edge” approach.

- Or, if the answer is that you’ll make better progress by going it alone, then you do that and you don’t give it a 2nd thought. The goal is to use the most efficient means to produce your platform or foundational software, not score points on hacker news.

Many startups through the years have been tripped up by this step, misguidedly believing that their foundational software was so great that once they released it, thousands of developers would step over each other to contribute to a project.

In the world of LLMs and generative AI, there is an additional consideration: do you absolutely need the latest models from Google, OpenAI, or elsewhere, or can you get by with slightly older models less constrained by usage restrictions? Can you use your own training and weights with off-the-shelf open source models? If you’re building a product that relies on agentic workflows, you’ll have to consider end user needs and preferences, but you’ll also have to protect yourself from downstream usage contraints, which could hit you if you reach certain thresholds of popularity. When starting out, I wholeheartedly recommend having as few constraints as possible, opting for open source models whenever possible, but also giving your end users the choice if they have existing accounts with larger providers. This is where it helps to have a platform approach that helps you address product-ecosystem fit as early as possible. If you can build momentum while architecting your platform around open source models and model orchestration tools, your would-be platform contributors will let you know that early on. Having an open source platform approach will help you guide your development in the right direction. Building your platform or product foundation around an existing open source project will be even more insightful, because that community will likely already have established AI preferences, helping make the decision for you.

To summarize, find the ecosystem that best fits your goals and product plans and try to build your platform strategy within a community in that ecosystem, preferably on an existing project; barring that, create your own open source platform but maintain close proximity to adjacent communities and ecosystems, looking for lift from common users that will help determine platform-ecosystem fit; or build an open core platform, preferably with a set of potential users from an existing community or ecosystem who will innovate on the edge, using your APIs and interfaces; if none of those apply, build your own free-to-use proprietary platfrom but maintain a line-of-sight to platform-ecosystem fit. No matter how you choose to build or shape a platform, you will need actual users to provide lift for your overall product strategy. You can get that lift from core contributors, innovators on the edge, or adoption from your target audience, or some combination of these. How you do that depends on your needs and the expectations of your target audience.

Up Next: open core on the edge and free products.