Some things appear in hindsight as blindingly obvious. And to some of us, perhaps they seemed obvious to the world even at the time. The observations of Copernicus and Galileo come to mind. To use a lesser example, let’s think back to the late 2000s and early 2010s when this new-fangled methodology called “devops” started to take shape. This was at a moment in time when “just-in-time” (JIT) was all the rage, and just-in-time continuous integration (CI) was following the same path as just-in-time inventory and manufacturing. And just like JIT inventory management had some weaknesses that were exposed later (supply chain shocks), so too were the weak points of JIT CI similarly exposed in recent security incidents. But it wasn’t always thus – let’s roll back the clock even further, shall we?

Party like it’s 1999

Back when Linux was first making headway towards “crossing the chasm” in the late 90s, Linux distributions were state of the art. After all, how else could anyone keep track of the all the system tools, core libraries, and language runtime dependencies without a curated set of software packaged up as part of a Linux distribution? Making all this software work together from scratch was quite difficult, so thank goodness for the fine folks at Red Hat, SuSE, Caldera, Debian, and Slackware for creating ready-made platforms that developers could rely on for consistency and reliability. They featured core packages by default that would enable anyone, so long as they had hardware and bandwidth, to run their own application development shop and then deliver those custom apps on the very same operating systems, in one consistent dev-run-test-deploy workflow. They were almost too good – so good, in fact, that developers and sysadmins (ahem, sorry… “devops engineers”) started to take them for granted. The heyday of the linux distribution was probably 2006, when Ubuntu Linux, which was based on Debian, became a global phenomenon, reaching millions of users. But then a funny thing happened… with advances in software automation, the venerable Linux distribution started to feel aged, an artifact from a bygone time when packaging, development, and deployment were all manual processes, handled by hand-crafted scripts created with love by systems curmudgeons who rarely saw the light of day.

The Age of DevOps

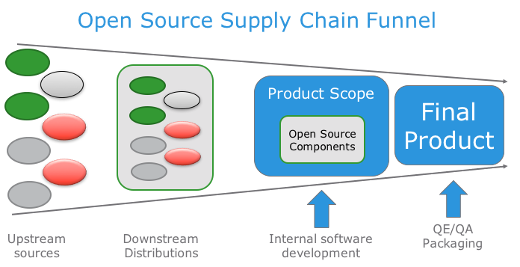

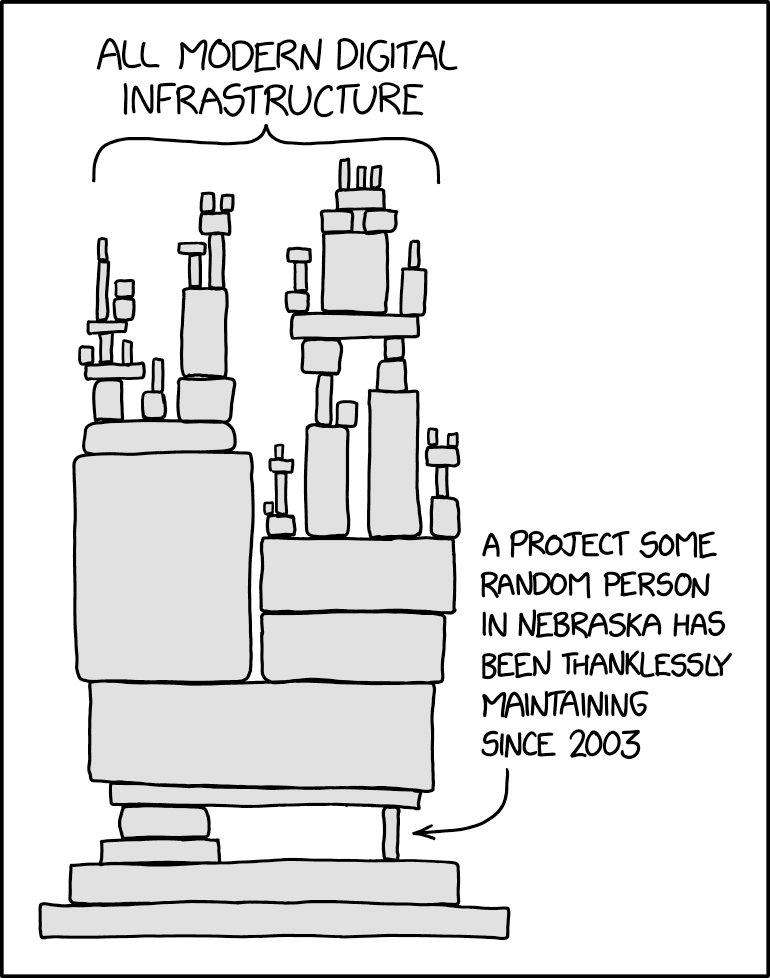

With advances made in systems automation, the question was asked, reaching a crescendo in the early to mid-2010’s, “why do we need Linux distributions, if I can pull any language runtime dependency I need at a moment’s notice from a set of freely available repositories of artifacts pre-built for my operating system and chip architecture? Honestly, it was a compelling question, although it did lead to iconic graphics like this one from XKCD:

For a while it was so easy. Sure, give me a stripped down platform to start with, but then get the operating system out of the way, and let me design the application development and deployment layers. After all, any competent developer can assemble the list of dependencies they will need in their application. Why do I need Red Hat to curate it for me? Especially when their versions are so out of date? The rise of Docker and the race to strip down containers was a perfect example of this ethos.

A few incidents demonstrated the early limitations of this methodology, but for the most part the trend continued apace, and has remained to this day. But now it feels like something has changed. It feels like curation is suddenly back in vogue. Because of the risks from typo-squatting, social engineering hacks, and other means of exploiting gaps in supply chain security, I think we’ve reached somewhat of a sea change. In a world where the “zero trust” buzzword has taken firm hold, it’s no longer en vogue to simply trust that the dependencies you download from a public repository are safe to use. To compensate, we’ve resorted to a number of code scanners, meta data aggregators, and risk scoring algorithms to determine whether a particular piece of software is relatively “safe”. I wonder if we’re missing the obvious here.

Are We Reinventing the Wheel?

Linux distributions never went away, of course. They’ve been around the whole time, although assigned to the uncool corner of the club, but they’re still here. I’m wondering if now is a moment for their return as the primary platform application development. One of the perennial struggles of keeping a distribution up to date was the sheer number of libraries one had to curate and oversee, which is in the tens of thousands. Here’s where the story of automation can come back and play a role in the rebirth of the distribution. It turns out that the very same automation tools that led some IT shops to get too far ahead over their skis and place their organizations at risk also allow Linux distributions to operate with more agility. Whereas in the past distributions struggled to keep up the pace, now automated workflows allow curation to operate quickly enough for most enterprise developers. Theoretically, this level of automated curation could be performed by enterprise IT, and indeed it is at some places. But for teams who don’t have expertise in the area of open source maintainership or open source packaging, the risk is uncertain.